Lágrima-Pantera, a silent and almost lost film by Júlio Bressane, had its first public screening on August 25, 2023 at the Cinemateca do MAM [Rio de Janeiro’s Modern Art Museum film archives], 50 years after it was made, as part of a retrospective of Bressane’s work, in its complete and restored version of 71 minutes, concluded in the early 2000s. It is available online in a smaller version, with a very different editing and in a low quality copy, from a broadcast for the Italian TV channel Rai 3. The definitive cut stands out for having its first half in black and white and the second in color, with the film also being more linear as it is more guided by the chronology of the shooting. Still, there are intercalations of times and spaces. The cut available online does not follow this chronology, containing various intercalations of time, space and colors.

The title of the film is inspired by a verse from O Guesa Errante by Sousândrade, “lágrima-pantera” [“tear-panter”], recognized by the director as two images of fear and trepidation, words with the same number of letters, joined by a hyphen, but difficult to put together. [1] Filmed between New York, Monroe County and Brazil, during the director’s exile, photographed by Miguel Rio Branco, using as the main set the apartment of Hélio Oiticica, actor in the film alongside Cildo Meireles, Rosa Dias, Bob Grass, Honey and Patricia Simpson, the project is inspired by the short films made by Hélio on several super-8 reels. In his text Arte da Memória, Bressane states that “these small films (2, 3 minutes) caught my attention, I saw in them a way of disappearing, of unlearning, of letting go of myself, of the cliché, of starting over….”

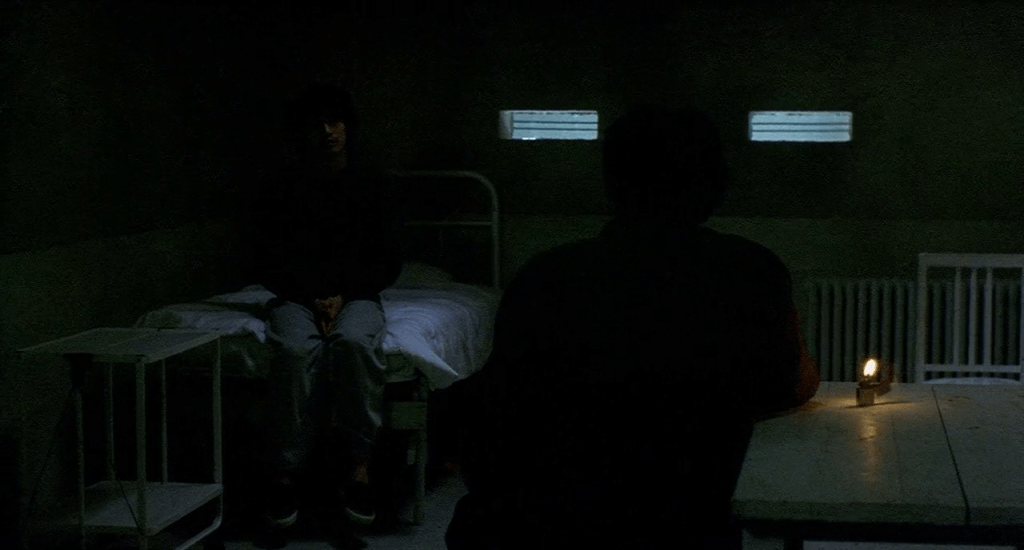

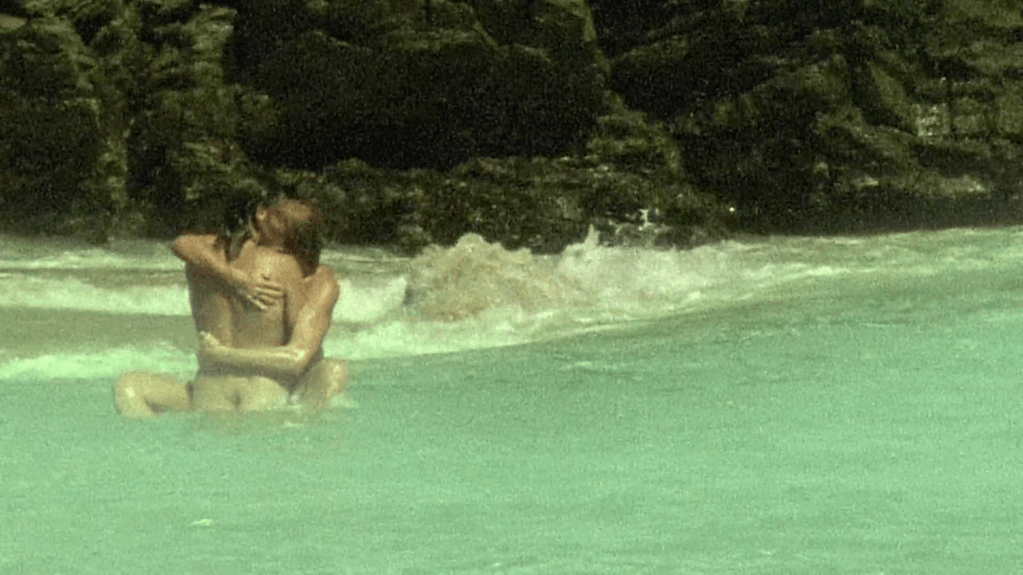

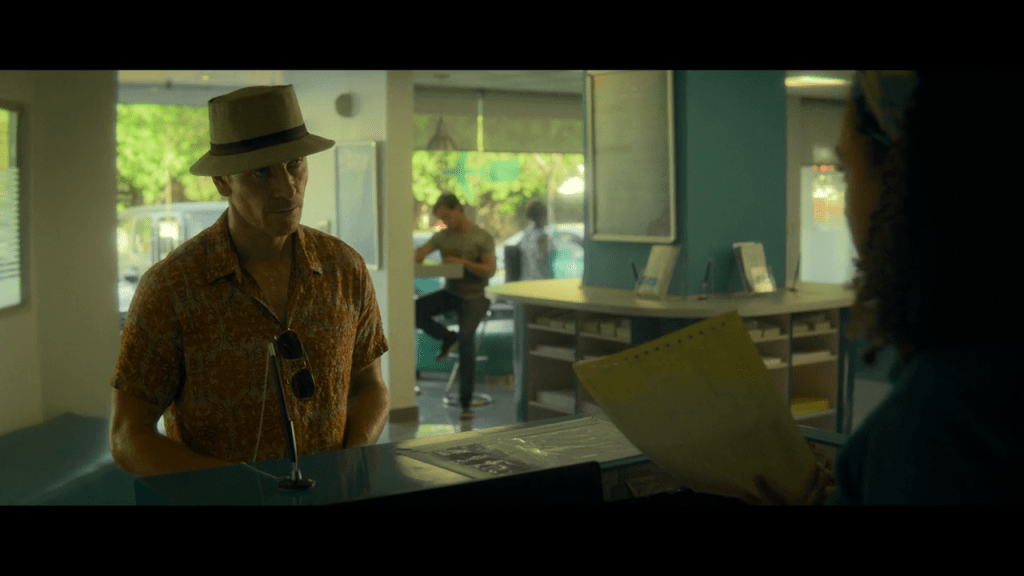

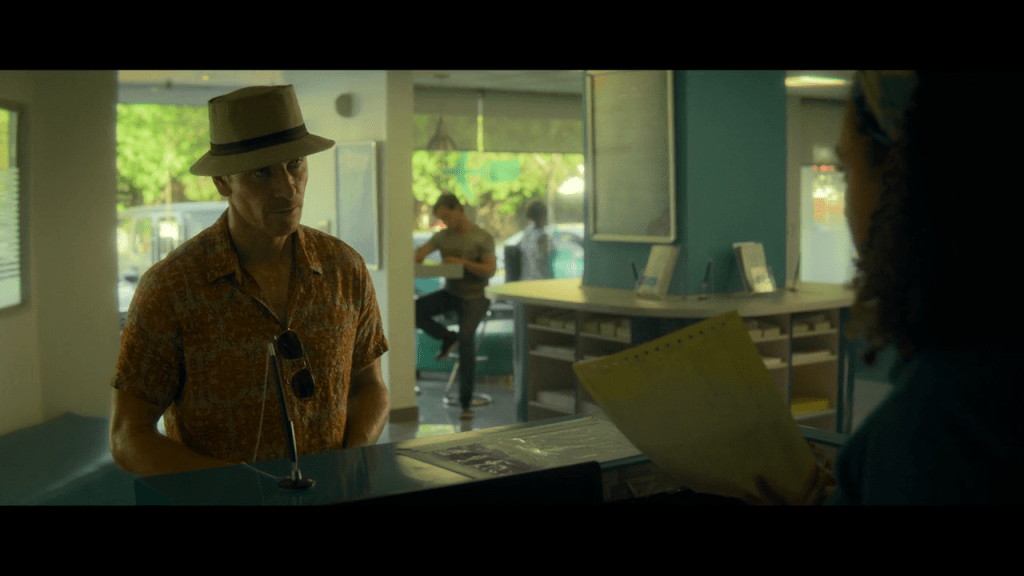

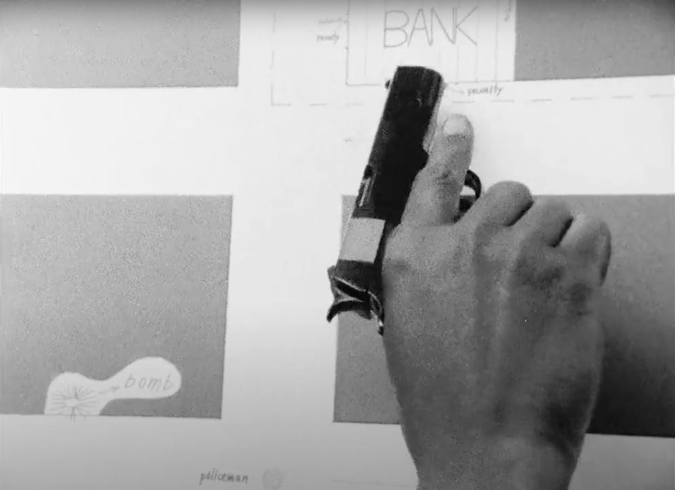

For Bressane, this urge to unlearn, to use the camera like a musical instrument played for the first time, leads to a tension between cinema in its various possible manifestations and an escape from it. Lágrima-Pantera initially presents a small intrigue involving three women and four men (one of them being Júlio Bressane), who live in a loft; the women intertwine feet and tongues and the men plan a bank robbery. [2] One of the women stops making out and looks at the camera, leading it in front of her using manual gestures that seem to hypnotize the operator, directing him to the next room. There, the men of the house meet, pointing with a gun at a cardboard with an amateur cartographic drawing of the surrounding streets of a bank and indications that reveal a robbery plan. In a single sequence shot we are quickly and superficially introduced to a romance, a kind of illusionistic hypnosis, and a planned robbery. Bressane seems to be guided by the following trigger: to abandon the idea before it becomes established as such, allowing oneself to be led with each shift by a new idea.

If at first the unlearning centers on certain themes and cinematographic genres, it quickly moves to the field of form and materiality. By leaving these intrigues aside, or at least by not addressing them head on, the film finds de-dramatization in the inertia and everyday life of that group. Cigarette smoke generates a lot of movement in the image and marks the passage of time. As soon as the film comes across the diary-film form, Bressane proposes still shots of men’s faces, briefly flirting with portrait films and even Andy Warhol’s screen-tests. By abandoning the initial questions of representation, he is faced with the more documentary levels embedded in the sequence shot and the experimental propositions that often accompany them. But of course, Lágrima-Pantera will not definitively fall into any of these definitions, continuing its construction process through abandonment.

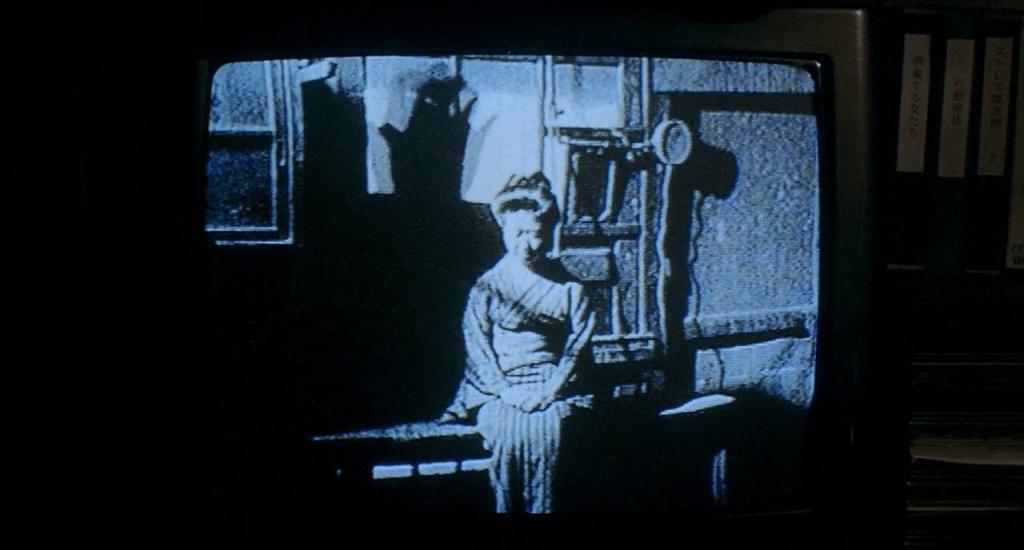

The film branches out, presenting more and more questions based on the means of exhibition and the means of composition that surround cinema. Both the disjunction of cinematographic elements through an installation method (screen, projection, scenic organization and bodies arranged independently as in a gallery room), as well as television with its also installation-like nature of embedding a film in an everyday environment, deforming the original format of images and sounds, seem to be approached as paths that distract Bressane from cinema, but also very thought-provoking and creative in their recompositions. On the television, we see excerpts from films, many of them police films, and routine programming from American channels, echoing the initial theme of the crime, without continuing the actions of the robbery plan. In many scenes from the group’s daily life, a small projector is used by one of the members to project films on other members or in unusual spots of the place. At one point, the projector is pointed directly at the camera lens and vice versa. In Hélio’s loft, there are many materials used in the artist’s installations, which are sometimes arranged in the rooms like a gallery work. A clear example is a room that contains transparent colored fabrics hanging from ceiling to floor, surrounding a bed, sometimes being used as a screen for hollow projections.

Gradually, the images become more abstract, with points of interest that are less and less explicit or even absent, filming everyday objects so closely that we can barely identify them. In these moments, Lágrima-Pantera finds itself on the limits of non-representation and non-figuration. When previous elements are revisited, they present themselves in their most material sense, tangentially evoking their fictional character: the cartographic drawing is no longer on the wall, but passing from hand to hand, like an object as everyday as a cigarette. None of these actions move the planning of the robbery forward. We no longer even know if the actors still play or if they just live their real lives in the loft. In the first part of Lágrima-Pantera, unlearning is closely linked to the planning level, to the moments that precede the full realization of the cinematographic project and that no longer belong to everyday life. Evidently, the film finds a new artistic path, located in the time when it was no longer just about life, which already began as an artistic project, but which has not yet been fully realized due to constant abandonment.

The intrigues introduced at the beginning are abandoned, but not forgotten; its echoes are inevitable and sometimes induced by Bressane (crime films on television, for example). The spectator keeps in suspension the yearnings introduced by the narrative drama, waits for the resolution of the robbery, for the manifestations of these loves that can more accurately denote the relationships of these people, for the clarification of the objects filmed very closely, for clarity in relation to what is reality and what is projection within the image, or, as a last resort, for the woman to return and, with her hands, hypnotize the camera again, returning it to the tracks of the narrative. While the crime is not followed by evidence, the montage suggests likely alternatives to the completion of the act through a narrative twist, whether due to the long absence of the men inside the house, or due to the chase and action scenes shown on TV. Every line introduced and not continued remains in a state of suspension after abandonment, based on a key question: has everything that was unlearned and abandoned continued by itself outside the field in terms of narrative?

It is possible to compare the form and aspiration of this first part of the film with the work Grande Núcleo (1960-1966) by Hélio Oiticica himself, composed of a series of suspended yellow quadrilateral plates that never quite configure closed three-dimensional shapes. In fact, they barely touch each other in their organization, but they still form a nucleus due to the proximity of these parts in relation to the exhibition space. It suggests a gravitational center for these pieces, which would designate their total shape, which cannot be perceived by observing the parts, but rather by the analogous shape on the recessed floor, like a small “step” below the ground. While the yellowish planes do not manage to compose three-dimensional forms of volume in space, another form, a framing form, is configured in another space, on the floor, and even this “outside” form, belonging to another field, does not work as a support base for the suspended parts. Returning to Bressane’s film, by being guided by unlearning, by scenes of similar matter that never fully connect to establish a form, but rather operate through their absence, cinema emerges reflexively in another space, secretly connecting all the elements that make up the film. Or, borrowing the director’s recurring statement: “cinema is hidden in films”. [4]

We’ve abandoned the apartment. The nighttime images of the city take over the film in static shots moving around its interior on the bright New York nights, full of artificial lights. The characters are eventually abandoned or eclipsed by the ellipse. New image movements are revealed outside the loft, presenting a pictorial drama of its own, destined to also be abandoned. The lights gradually become more abstract and less dramatic until the summit in a blurred plane in which bouquets of light move very slowly in the distance. After dispelling the dramas and stimuli of the inner scenario, the same is done with the outside world. This first part of the film ends with a car trip to an airport and a plane ride afterwards, bidding farewell to the black and white image.

The film ends. Or almost. A cardboard ornament, similar to a mobile, created by Oiticica, announces the credits: on one side of the work the team involved is listed, on the other, the title “Lágrima-Pantera” and the enigmatic subtitle “a míssil” [“the missile”]. The film gains color. We review some of the internal scenes, now in color, combined with new ones. Everything becomes vibrant, not only because of the coloring, but because now everything resonates like an uncompromising echo of the first part of the film, without the dramatic weight presented previously. Bressane appears in front of the camera and joins the actors to smoke. Untied and relaxed, the film now slightly follows a new direction. If the first part approached a notion of closure, both due to exhaustion and the symbolization of the end of the journey, Bressane turns the corner in the final moments, proposing a turning point.

While the first part of the film is located in the passage from life to performance, metaphorized by the robbery that is never fully carried out, now the film is located in the transition from performance to life, like the backstage after the act, which now returns to little by little into everyday life as if fantasies and roles were removed. The film moves away from the initial project of the first part, the echo now focuses less on the fictional character and more on the awareness that the group has already presented itself as a film crew and actors, yet they casually resume remnants of their previous roles (for example, example, women posing for the camera with a gun in their hand).

The idea of the camera as a new instrument for the filmmaker is continued in this new stage of the film. The documentary aspect is quite amateurish, also with no pretensions to accuracy in the framing, and does not present clear points of interest in the landscapes they cross, nor does life seem to be the objective of filming, distancing Lágrima-Pantera from the diary-film, as if the unlearning was now applied to life itself and no longer to cinema.

Underlined by the constant presence of the car as a narrative guide, the film moves quickly as if crossing a single straight line, without curves, like a directed missile that no longer cares about exhausting the stages of the film, just touching them. The homemade registers now move between a house with a garden in suburban Monroe County, the loft with a balcony in central New York and two other residences. The way the external and internal areas of these properties are presented is confusing due to the agility with which they are shown and navigated. The film traverses spaces without the need to clearly locate the viewer. Even operating through unlearning, in this new stage the film seems to continue with more determination as if heading towards a new unknown objective.

A possible loose interpretation takes up the initial intrigue of the film: the robbery, never shown, may have been carried out successfully off the field, the group now continues on an automobile escape through the cities – in fiction, because of the crime, but we can also think about political exile – and even with money from the bank robbery to now film in color. The next stop is an aristocratic landscape, the wide fields contrast with the crampedness of the previous properties, and Júlio Bressane walks elegantly wearing warm clothes and a hat. With freedom and no sense of escape, he films himself. There is happiness and fulfillment.

The sun goes down. The cycles of the sky point to yet another end. From the window of an airplane, we fly over the clouds. Despite the total lightness that the film achieves, at a time when the fiction and intrigue seem to have completely drained away, an insertion is repeated twice. A shot in Brazil, Bressane’s home, in which a dog jumps with joy playing with a man, the director’s father. Suitcases are removed from the car indicating that someone has returned from a trip. An image that calls into question the chronology of the film; the tone is melancholic and nostalgic, going back both to a distant place, in a past before the film, access prevented by political circumstances, and to a future moment in which the director would return to his country of origin. The presentation of the image through insertion displaces it from the whole, granting an indefinite temporality.

The film that was so reluctant, following the paths of unlearning, finally emerges when it frees itself from constant abandonment; the idea of abandonment is abandoned. As Júlio has said a lot in the speeches that accompany the screenings of his films: “Cinema appears when the film disappears.” However, the great strength of Lágrima-Pantera (words that bring back pain and fear), seems to be precisely in the intertwined moment in which we find, simultaneously, both cinema and life itself, finally surrendering to both, making the film disappear for good. The enigma behind “the missile” and why there was such a rush in this second trajectory then seems resolved: “I miss you” is the closest the English language has come to our word “saudade”. It is with this final fragment of grace and fulfillment that A Longa Viagem do Ônibus Amarelo (Júlio Bressane and Rodrigo Lima, 2023) begins.

Gabriel Linhares Falcão

Notes:

[1] As the director describes in an interview with Revista Limite. Available at: https://limiterevista.com/2024/04/14/conversation-with-julio-bressane-part-i/

[2] The version available online begins with a short shot of L’Atalante (Jean Vigo, 1934) and another short shot of Bressane on a film set, while the final version shown at the MAM Cinematheque opens with a shot fixed night view of the moon between well-lit clouds.

[3] There is a long shot of the opening credits of Don Siegel’s The Killers (1964).

[4] In an interview with Folha de São Paulo, in October 2023. Available [in Portuguese] at: https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/ilustrada/2023/10/o-cinema-esta-oculto-nos-filmes-diz-julio-bressane-premiado-na-mostra-de-sp.shtml