I usually find that the beginnings of films are their best parts. In the best cases, we enter an entirely new world, whose internal dynamics have already been established before our arrival, and whose rules of operation we are not yet familiar with. This initial strangeness generally lasts a short while, but not in the case of Jerzy Skolimowski’s films. In these, not only is the initial understanding of what the film is about postponed, but when we finally manage to understand what is happening, this world is already shaping into something else.

His plots start from realistic scenarios, although sometimes unusual for a film, which are gradually taken to an extreme, stripped of their masks of civilization: a young man’s sexual awakening at his first job, at a public pool in London; a hairdresser in Brussels looking for a Porsche to compete in a rally; the renovation of a London house by illegal Polish immigrants; a wanderer arriving in a village in rural England; an Afghan fleeing from the American army in a Polish forest; the journey of a donkey through Europe. Soon, any semblance of normality that could exist in such premises is distorted by the characters’ restlessness – carnal desires, cravings for power and control, murderous instincts, pain, hunger, fear. The only constant in these stories seems to be their inconsistency, their continuous movement.

The filmmaker’s own trajectory, moreover, seems somewhat governed by the same principle of variability. Born in Poland, where he began his career, Skolimowski made films in Belgium, England, Germany, and the United States, as well as co-productions between two or more countries. Before starting to work in cinema, he was a boxer and a writer, and he occasionally works as an actor, in some of his own films and in Hollywood productions such as Mars Attacks! and The Avengers, or in independent productions like David Cronenberg’s Eastern Promises, where he plays a Russian immigrant, ex-KGB, in England.

Beyond the singularity of the plots of his films, each of them is also made in a distinct production context. Languages, countries, circumstances, and budgets change; however, we cannot say that Skolimowski adapts to each new environment. His films, as distinct as they may be, share precisely a sense of estrangement. Each experience is new and alien, whether it be entering a foreign country, a forest, or a swimming pool. Each new setting is also a potential stage for experimentation, each new object a possible prop. When his films stray from their realistic premises, it is primarily towards plastic inventions, crafted with lights, paints, glass, mirrors, water, always within the diegetic realm.

Moonlighting (1982)

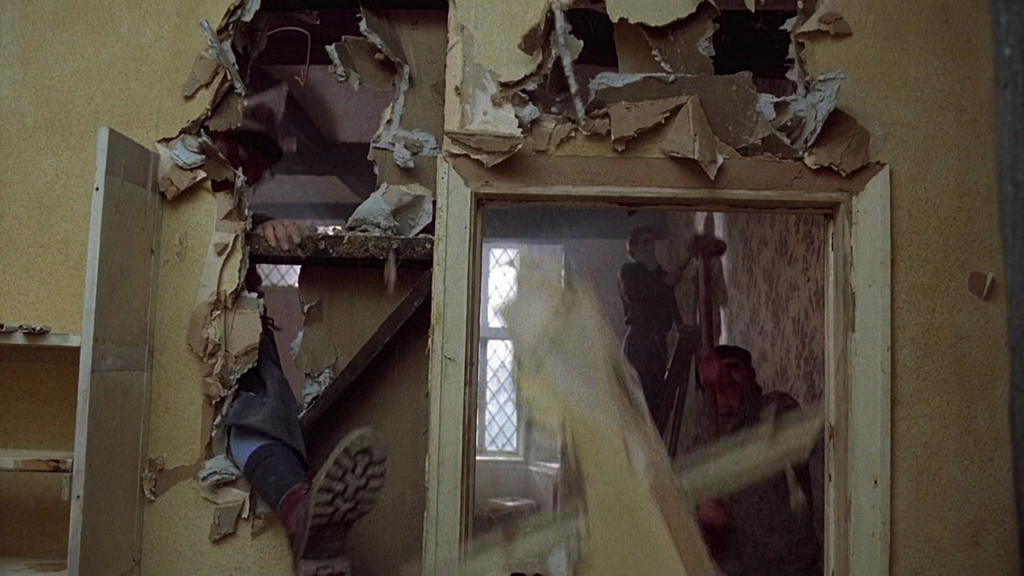

Moonlighting (1982) perhaps exemplifies the filmmaker’s peculiar character better than any of his other productions. The strangeness of the film, set in England, is found in a situation that seems initially banal: the characters’ lack of understanding of English. Four Poles go to London to work on a house construction project, without work visas. Nowak (Jeremy Irons), as the only one among them who speaks a little English, becomes a kind of leader; in the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king. It is from this advantage of the character that the plot will unfold.

Given the illegal status of their stay and the fact that, during it, Poland enters a period of martial law, Nowak’s initial everyday control over the other men quickly takes on authoritarian proportions. He keeps the other three isolated in the house and ignorant of the unstable situation in their home country. Nowak becomes a sort of manipulative media, being the only communication link for the others with the outside world, deciding what food, money, and information comes in and goes out. The situation reaches such an extreme that Nowak starts to control even his companions’ time, changing the clock’s hours, reducing their sleep time, and lying to them to finish the construction work quickly.

Interestingly, the protagonist does not use this power for his own gain; on the contrary, everything he does seems to be aimed at maintaining an illusion of normality within the house. He has a job to do and he won’t interrupt it, even if his country no longer exists, even if there is no reason to return, that is his only purpose. To maintain appearances within this isolated system, Nowak will put himself in absurd situations outside the house. When the money their employer gave them begins to run out, for instance, he creates a complex operation to steal food from the supermarket. We follow these events alongside the protagonist’s voice-over, with his direct narration, which, although subjective, only reinforces the objective nature of his actions and plunges the viewer even more deeply into this delimited world.

The four Poles are constantly seeking solutions to their problems, always concrete: while Nowak ventures into the streets looking for ways to take the double amount of food from the supermarket without the manager noticing, his companions destroy and rebuild the entire house, so that the setting, like the narrative, is in constant transformation. The first thing the men do when they arrive at the house is to reuse a beer can as a pot, already indicating that everything here will be reused. Skolimowski will renew the narrative in the same economic logic, with the same elements already in play, rearranging them like a Rubik’s Cube. At the end of the film, Nowak uses the same technique he developed to steal from the supermarket – hiding goods somewhere in the store to come back for them later, pretending they were his – to steal a scarf, the only item he takes for personal use throughout the film.

These issues are not small anecdotes in the characters’ trajectory, minor situations in the face of the larger narrative; as in Hollywood’s action or comedy movies, they consist of the core of the film, what drives the intricate plot forward. In both cases, the story itself matters less than how its characters deal with elements on the scene. The difference lies mainly in the nature of the limitations in Skolimowski’s film, which are not spectacular adversities like terrorists or thieves, but rather time and money. Interestingly, despite being more realistic, these adversities are more abstract than the personified enemies of Hollywood films, as they cannot be directly confronted. Also abstract, in a way, is the spatial limitation in Moonlighting: there is nothing physically preventing the characters from knowing the rest of London or even returning to Poland, what limits them are the laws (the fact that they are in the country without a visa, the martial law in their home country) and the foreign language.

It is through this unique mixture of realism and absurdity that Skolimowski’s work also approaches Kafka’s literature, which, in the words of Gunther Anders, “disrupts the apparently normal appearance of our crazy world to make its madness visible. However, it manipulates this crazy appearance as something very normal and, with that, even describes the crazy fact that the crazy world is considered normal.” [1] In a similar manner to Nowak, Gregor Samsa is more concerned with missing work and more preoccupied with the difficulties of getting out of bed with his new body than with the fact that he has become a monstrous insect. Skolimowski’s viewer, like Kafka’s reader, is inserted into a strange world without explanations, as are often the characters of both, although they simply deal with the consequences of this world more than question it [2].

Le Départ (1967)

Skolimowski’s characters, in general, have a single goal that borders on obsession, and they will do anything to achieve it. In this pursuit, the most absurd – and at times unnecessary – actions are undertaken. While initially part of a narrative simplification that reduces the plot to a single vector, this ultimately leads to an opening for different and unlikely possibilities of continuity. Wherever the characters go, whatever situation they find themselves in, the environment comes into play as much as they do; everything blends together, the film is moldable material.

His films usually feature protagonists whom we follow throughout their entire duration, who seem more submissive to the whims around them than to have any power of transformation. EO‘s donkey (2022) may be the most emblematic example in this case, being entirely subject to humans, given the submissive condition of the animal [3]. However, the system is not rigid, and there are characters who seem to have more autonomy, such as Jean-Pierre Léaud in Le Départ (1967).

While Moonlighting works from the material restrictions of the characters in a fixed setting, albeit in constant mutation, in Le Départ we seem to be facing an animated cartoon, with Léaud jumping from corner to corner of Brussels like the Road Runner. What motivates him, after all, is also a limitation, of the same order as the later film: money. But his ends and, mainly, his means, are very different. Léaud’s character Marc, a hairdresser, is in search of a Porsche to compete in a race, and will try to get it in unusual, humorous ways, accompanied by a young woman he meets along the way.

Unfolding in time, after all, and not just in space, it is the film that is in constant mutation, in constant movement. This movement is peculiar, not necessarily rectilinear. The characters bounce around the city while the plot is also shaped in an organic, malleable, random way. A mirror breaks amid the couple’s playfulness, but in the same shot we see it being reconstructed in a rewind, as if nothing had happened. Later, it is even sold whole in a used items store. In the real world, this glass indeed broke, but in Skolimowski’s world, even time can be molded. This is not a filmmaker concerned with recording reality, but with sculpting his own.

The Shout (1978)

The story of The Shout (1978), adapted from a tale by Robert Graves, begins to unfold during a cricket match in a mental institution, and our impression is that everything here is related in a intricate and autonomous way, much like in the game. Patients and staff play side by side, just as madness seems to walk hand in hand with sanity in the story of the shout that gives the film its title, narrated by one of the patients, Crossley (Alan Bates). Given his condition of insanity, he is evidently an unreliable narrator, casting doubt on the truthfulness of the entire narrative to follow; he himself starts the account by saying that the story is always the same, even though he tells it in “different ways, changes the order of events, varies the moments of climax.” He does this, he continues, “because he likes to keep it alive,” a procedure that resembles Skolimowski’s own, who also seems to stir his plots with the same intent.

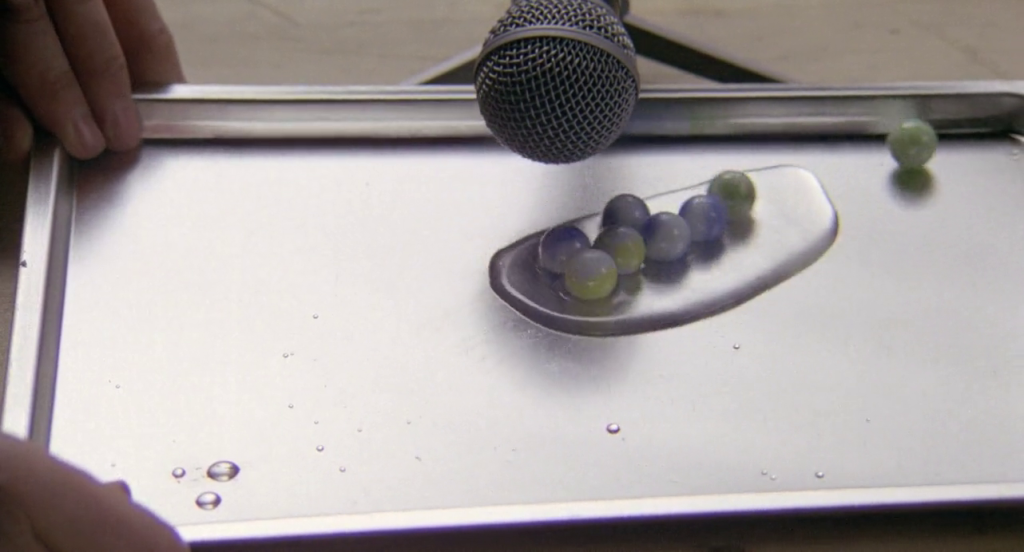

The foreigner in the story is Crossley himself, a wanderer from Australia, who invades the life of a couple in rural England, Rachel (Suzannah York) and Anthony Fielding (John Hurt). Anthony spends most of his time in his studio, where he creates experimental music by recording distorted sounds of different combinations of objects; rolling marbles in a tray of water, drawing a violin bow across a torn aluminum can, or lighting a cigarette very close to the microphone. Just as the beer can is transformed into a pot in Moonlighting, the marble, the violin bow, and the other objects that accompany them are transformed into musical instruments. When Crossley arrives in town and later at the couple’s house, he claims to have learned from an Aboriginal shaman a powerful shout, capable of killing, among other spells. He even tells Anthony that his music is nothing compared to the shout, which prompts Anthony to ask to hear it.

The two go to an isolated spot amidst dunes surrounded by the sea, where Crossley finally shouts, a sound that comes as a graft, difficult to describe; high-pitched and intense, like many voices screaming at once or, still, assuming that it was made in a similar way to Anthony’s experiments, it could be the noise of some kind of air suction device. The unreal aspect of the shout becomes more interesting precisely because we have witnessed the creation of unusual sounds beforehand, establishing a precedent. The sound representing the shout certainly has a fantastic quality, since its true source is omitted and it is attributed to Alan Bates’s character, but it is made of the same material as the sounds produced by ordinary objects. It stands out from the premise of reality assumed in the film up to that point, but this premise was already far from a perfectly flat surface; it already had its undulations.

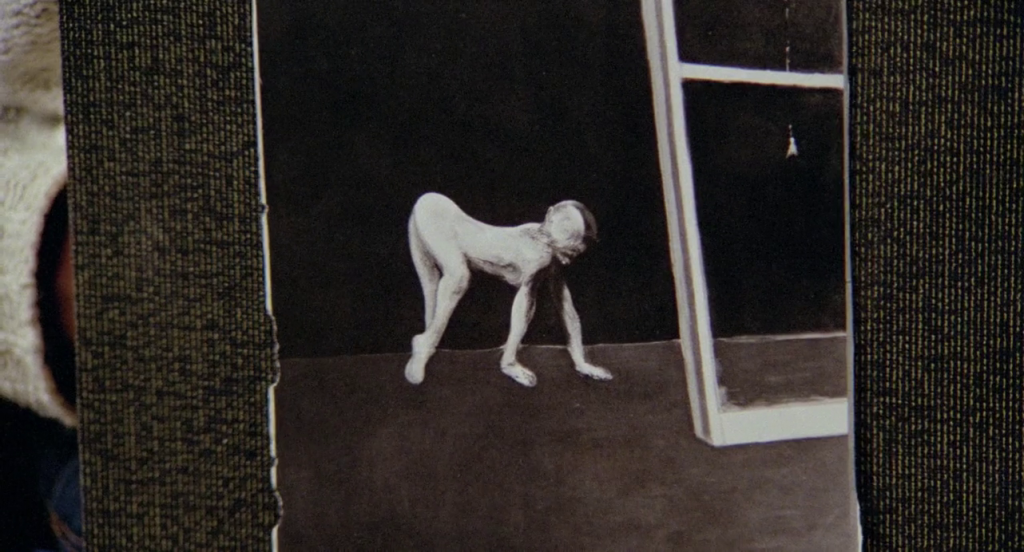

Proving that it indeed has supernatural powers, the shout leaves Anthony catatonic. Returning to the house, Crossley seduces Rachel, apparently also in a magical way, stealing a clasp from her sandal, leaving her entirely submissive to him, in an almost savage manner. At one point, she walks naked, on all fours, behind Crossley, her body configuring itself very similarly to Francis Bacon’s painting Paralytic Child (1961) – a painter in whose work shouting was a recurring theme – from which Anthony has a print in his studio. When this happens, the image appears in black and white for a second, as if to mark such resemblance. To break the spells, Anthony must smash a stone that appears in his hands in the dunes, after the shout, an object that supposedly contains Crossley’s soul. Small clues like these seem planted everywhere, suggesting that magic may not be restricted to the figure of the wanderer but may be spread across elements that were already there before his arrival, or even, as Crossley himself suggests before starting his account, that the pieces are shuffled, implying that linearity is not so important in this story.

The narrative of The Shout is indeed fantastic, unlike Skolimowski’s other films, but his way of working it is not very different from the rest. Crossley’s madness or shamanism are just components of a larger, complex, and hermetic game, where everything seems to be related, everything seems to be alive, in a secret and mysterious functioning: cricket, the madmen, Anthony’s music, the landscape of dunes, the deep shout. Reality, again, is not fixed but composed of this mixture of strange and normal elements, sometimes orchestrated and controlled like in Anthony’s sound experiments, sometimes released with disruptive force in Crossley’s shout and in Bacon’s paintings.

Deep End (1970)

Skolimowski’s material crafting perhaps appears more emphatically in Deep End (1970). Already in the credits, we have an almost abstract mixture of elements seen up close: a drop of blood dripping gives way to red pipes and gears, through which the camera wanders until it reaches a metallic surface, where the face of a boy is reflected, finally covered by a hand dirty with blood. It cuts to a bicycle being ridden by the boy, Mike (John Moulder-Brown). He is going to his first day of work at a public bathhouse and swimming pool, where he will fall in love with another employee, a slightly older young woman, Susan (Jane Asher).

Horror and beauty will walk together in this journey of Mike’s sexual discovery, that culminates in murder. The bathhouse is, at the same time, a place of sensuality and disgust, where all boundaries blur. The nature of Mike’s work soon reveals itself to be ambiguous when Susan suggests that he should offer sexual services to their clients. These clients, much older than Mike and Susan, also seem to have no problem flirting with young people. A middle ground, neither entirely in the water nor out, like a suitable habitat for the metamorphosis from tadpole to frog, the bathhouse marks the passage from boy to man or young woman to woman. There, both characters will learn about the ways of the world at its most visceral level, where the world of sex is inseparable from the world of work. While Mike nurtures a platonic love for Susan, she betrays her fiancé with an older and married swimming instructor who teaches teenagers in the pool; both Mike and Susan seem to be at the bottom of the food chain, submissive to their elders in every sense.

The oscillation in Deep End mainly occurs in the relationship between the two characters, ranging from playfulness and flirting to rejection (on Susan’s part). Mike’s motivation is not as defined as the monetary goals of other Skolimowski’s characters but is marked by the inherent vagueness of desire: he wants Susan, blindly. The obstacles faced by the protagonist here are everything that threatens this desire, Susan’s boyfriends, her contempt, or even anything that tarnishes her image. When he goes out one night to find her, he comes across a life-size cardboard poster of Susan naked at the entrance of a strip club. Not only does Mike steal the poster, but he covers the image with a coat while carrying the object on the subway, where he follows Susan and questions her about the figure, incredulous.

The final confrontation between the two could not happen anywhere else but inside the swimming pool, in a scene that we will realize then takes place just before the opening credits of the film. They end up there after grappling in a snowy park, where Jane Asher’s character realizes she has lost her engagement ring. The two decide to try to find the ring in an inventive way, tracing a circle around where they grappled and collecting all the snow from there, depositing it in a bag. They take this bag full of snow into the empty pool, where they set up a complicated operation to find the ring: they use the heat from a lamp to heat a kettle with water, melting the dirty snow slowly inside Susan’s pantyhose, which serves as a sieve. The sequence as a whole, if not tied to a narrative context, would closely resemble what was being done in the art scene of the same period when conceptual art, performance, and land art emerged and thrived.

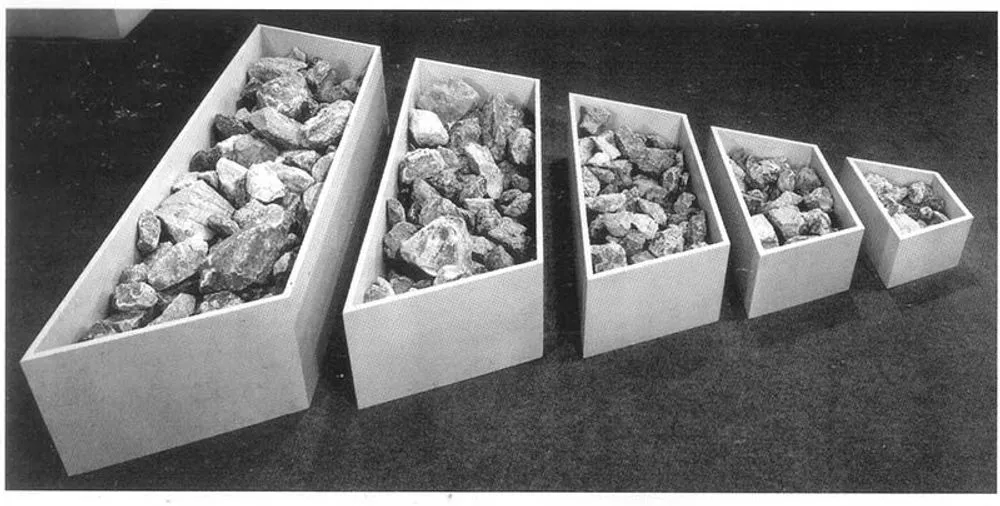

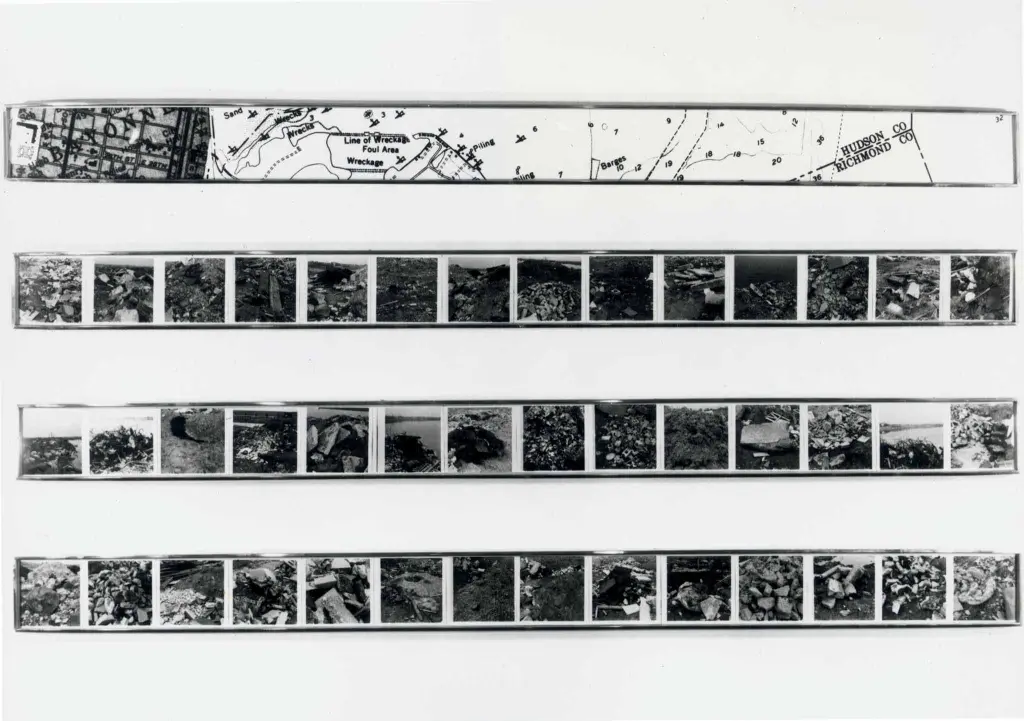

For example, we can consider the work of Robert Smithson, the father of land art, who in the 1970s essentially assumed two aspects: there were his interventions in the world, his famous land arts, and the fragments of the world he brought into the museum. In this second case are included his non-sites, in which he arranged earth and stones taken from landfill sites in the museum – accompanied by the record of this transposition process, displacement maps, photos of the sites, etc. This earth and stones were sometimes arranged in isolated mounds, sometimes accompanied by mirrors that expanded and confused their dimensions, sometimes inside delimited containers, in the shape of shelves or spacecrafts – despite dealing with such concrete and earthly elements, Smithson always had a penchant for science fiction.

Parallel to his artistic production, Smithson wrote essays about his practice, where a central theme was that of entropy. Commonly associated with an idea of disorder or chaos, entropy is somewhat more complex. Simplifying greatly, it is more a measure of randomness, of possible configurations, than randomness itself. One of the most common examples to explain it would be precisely ice melting: when water is frozen, its molecules are more organized and rigid; once exposed to heat, transitioning from the solid to the liquid state, the level of disorder of these molecules (entropy) increases until it reaches its maximum value, completely melting. In this state, the system is again in equilibrium, but if the water is exposed to more heat and begins to transition to its gaseous state, the level of disorder of the molecules will increase again.

The situation exemplifies the second law of thermodynamics, which states that “the entropy of any isolated thermodynamic system tends to increase over time, approaching a maximum value.” Entropy is usually associated, therefore, with the amount of energy lost in a process that generates heat – in the operation of a machine, for example, part of the energy spent will necessarily be lost when the machine heats up, not being converted into another usable form of energy.

The ice sequence in Deep End, which could also be a non-site – the swimming pool, after all, is very similar to “white cube” conception of the modern museum – can serve as a metaphor for Skolimowski’s work in general. His films are like closed systems (the public swimming pool, the work at the house, the search for a car to compete in the rally) in which molecules move in disorder (Jean-Pierre Léaud in Le Départ is a particularly agitated molecule) until they reach their maximum level (the scream in The Shout might be the most appropriate example here), and then settle down again. As in entropy, a level of energy is necessarily lost in this process. Although the characters act in pursuit of specific goals (no matter how foolish they may seem to us), the effort they make for it is notably greater than necessary; they will zigzag when they could walk in a straight line. You might be able to transform ice from a solid to a liquid state, but it is impossible to separate it from the earth, clean it, it’s all dirty and mixed up, molecules in motion and disorder.

After finding the ring, Mike puts it on his tongue and gets naked, inviting Susan to also undress to retrieve the object. It is implied then that they will begin intercourse, but the boy fails somehow: by the expression he makes, he reached his peak of energy too quickly. Susan tries to leave, and he tries to stop her, as the pool begins to fill up. Mike then pushes the heavy iron lamp towards Susan, who gradually falls dead into the water. The movement of the lamp also knocks over buckets of red paint. The red drop in the credits was then paint, not blood, but that matters little here, where both are, like the sounds in The Shout, made of the same filmic material. Susan’s lifeless body, Mike embracing it, blood, red paint, clothes, kettle, everything floats together in the pool.

Paula Mermelstein Costa

Notes:

[1] CARONE, Modesto. Introdução. In: KAFKA, Franz. Essencial Franz Kafka. Penguin-Companhia, 2011. p.13.

[2] “Kafka, for wiping the slate clean of artistic and psychological conventions and inventing a narrator equal to his characters: the unconscious or unwitting narrator, who knows as much as the character and the reader, that is, nothing or almost nothing, which leads them, through a strictly literary mediation, to the alienated universe in which we all live.” [Ibid, pp.8-9]

[3] I didn’t delve into the film here as I have already written about it in another text, in a past edition of the magazine, and for the Talent Press Rio in 2022: https://www.talentpress.org/bt/talentpress/v/do-mules-dream-of-electric-mules