In a psychiatric institution, a woman reads the beginning of Bluebeard’s tale, and claims to know how the story ends: in his murder at the hands of his young wife. A man, returning from work, passes through a tunnel, where he removes a pipe from the wall and takes it with him. In a dark room, he uses the pipe to kill a woman in bed. Next, detective Kenichi Takabe (Kōji Yakusho) arrives at the crime scene, surrounded by police officers, finding the woman’s bloody body marked by an X and, soon after, the man’s wallet, with his identity. While everyone is making plans to search for the culprit, the detective discovers him opening a little door in the hallway.

These opening five minutes already introduce us to the elliptical and synthetic character of Kyua (Cure, 1997) by Kiyoshi Kurosawa, which follows the investigation of a series of strange murders, like the one we have just witnessed. The killers are apparently normal people, who don’t hide their identities or deny their actions, but also don’t seem to have great motivations to justify them, as if they were acting under some type of trance. They mark their victims with an X-shaped cut at the neck, again without knowing the exact reason. All the clues point to an external factor, to some type of influence acting on them – some even mention that “the devil told them to do it”.

We only hear the end of Bluebeard’s tale, we don’t know how the story got there, how it ended in his death. The same can be said of the first murder we witness, Kyua’s starting point, and the movement that the film makes from there on will be backwards, gradually revealing what was omitted. This will be done slowly, so that with each new murder we become a little more familiar with the modus operandi of the crimes. In fact, each of these seems to offer more questions than answers, so that the aura of mystery never entirely dissipates, parts of the process remain unintelligible, others remain in the shadows.

Detective Takabe works together with forensic psychologist Shin Sakuma (Tsuyoshi Ujiki), trying in vain to find some kind of relationship between the killers. Frustrated with the lack of results, the detective even suggests to his colleague that perhaps there is something in common in the culprits’ past, some childhood trauma that justifies their actions. The proposal is absurd, both recognize it; This is not a case that can be deciphered by psychology, just as this is not a psychological thriller, despite starting from several premises of this sub-genre – a police officer consumed by both the case and his personal life, a series of murders in a city big, etc. Kyua will descend through his own hidden paths, in the same way that the film’s true antagonist, Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara), the “devil” who influenced the killers, uses psychology to enter its underworld, its “evil twin”, hypnosis.

His first appearance is also mysterious. On a beach, a man meets another who seems to have lost his memory, and takes him home. Mamiya is the name written on his coat, as he is then called. All the questions that the owner of the house asks Mamiya, who wanders around the house as if looking for its darkest spots, are countered with other questions, until finally he tells the stranger about his life, his wife. Mamiya lights his lighter – an act whose sound we hear louder than we should – which seems to mark our passage to another instance. The next morning, the wife will have been murdered by her husband, who then jumps out of the window.

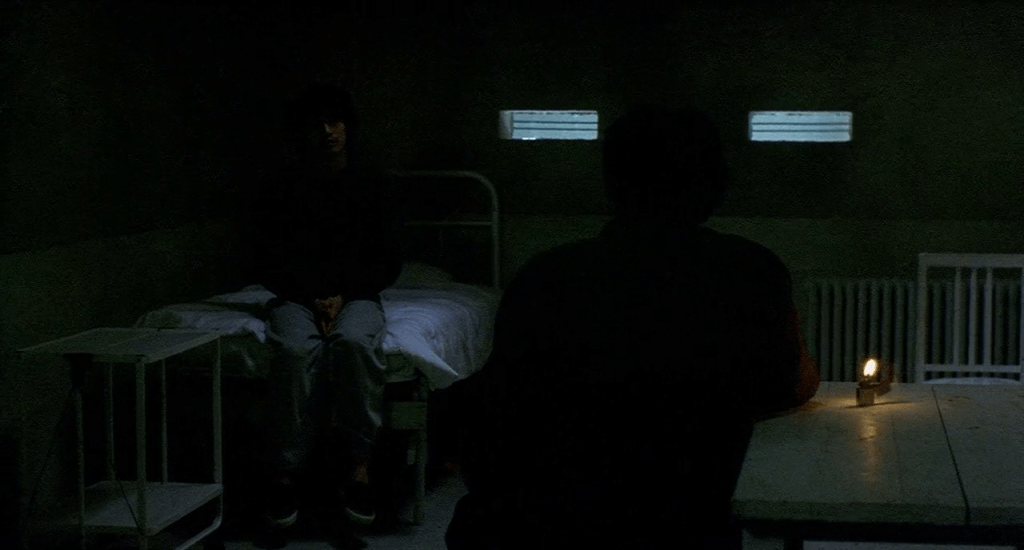

Mamiya is found on top of a roof and taken to a police station. There, we see the same process repeat itself: he claims not to remember anything and for each question the police officer asks him, he answers another question. But here, there seems to be a problem: there is another police officer in the room, who seems distracted writing something. When Mamiya starts working on his process, asking the police officer who he is, the other man stops looking at his papers and turns around, interrupting the hypnotic sequence. Mamiya will have to start over. He gets up, smokes a cigarette, and waits for the second police officer to leave the room before continuing. He sits in the chair where the man who left was sitting, turns off the light and lights his lighter. The next day, the hypnotized police officer will kill his coworker. Mamiya’s victims seem random, as if they weren’t even chosen by him, but rather mere coincidences resulting from where he ends up, where they take him.

As he is taken to a hospital, the next victim will be a doctor. A scene with the character earlier already suggests certain difficulties she, as a woman, faces in her work, when a previous patient mockingly suggests that the doctor’s request for him to lower his pants would be of sexual nature. Once attending to Mamiya, we see the process we are already familiar with unfold. As he cannot light a cigarette inside the hospital, he here resorts to tap water which he uses to fill a glass. The fire, then, was just a red herring. The ritual can be done with other elements. What seems to matter is more of a constancy of sound and subtle movement. Mamiya spills the water from the glass he just filled onto the floor. The doctor follows the path of the water, as do we, now in a close plane. It drips slowly, darkening the gray floor of the room it passes through, as if it had a life of its own.

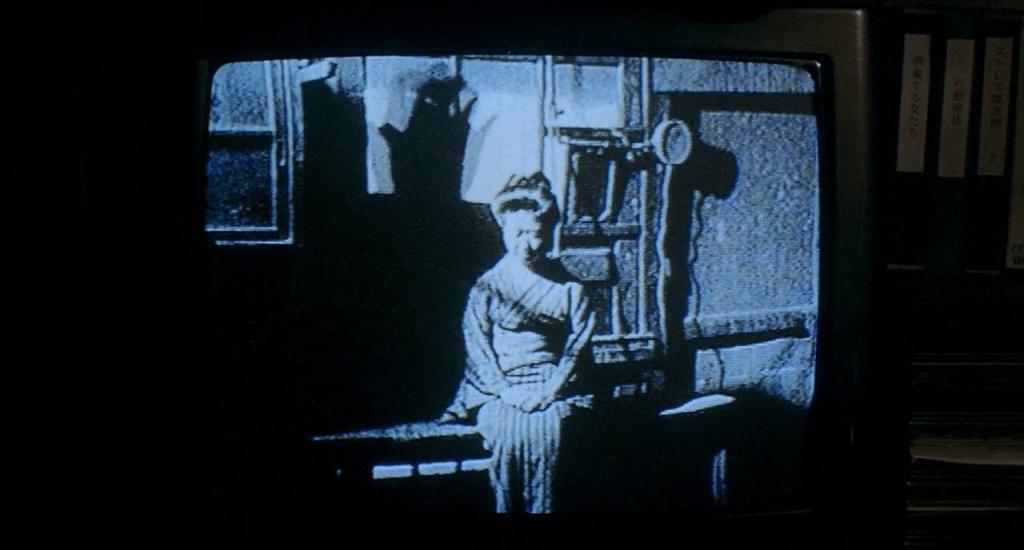

Mamiya’s process is similar to Kurosawa’s: he works with invisible things based on suggestions, using what he has at his disposal in each room to set up his scene. After all, his hypnosis ritual is like a scene, the only difference between this and theater or cinema is the level of involvement or submission that the spectator has with what he sees. The black water that gradually colors the floor or, at another moment, drips brightly from the ceiling, the small flame of the lighter, or the palpable darkness of the rooms, are active protagonists of the film’s body. The same can be said about the ancient media that Takabe finds throughout the plot: the late 19th century Japanese film that records a hypnosis, or the phonograph recording of what appears to be interrupted instructions for the ritual. Neither of the two records, with their grainy and distorted texture, their obscure and incomplete content, works as a clue to solving the case. They seem to be there much more for their value as signifiers than signifieds; and yet they do not serve a merely decorative role, but an affective, hypnotic one.

If the hypnosis ritual is represented here as a theatrical performance, these elements must be considered actors as much as the characters. As they drip, tremble, flash and slowly spread throughout the environment, they are tangible evidence of this process that would otherwise be invisible. It is important that this evidence is material since the ritual not only deals with invisible forces but does everything it can to naturally infiltrate everyday moments.

After pouring the water in front of the doctor, Mamiya already has control over the woman, and begins to bring up the frustrations she went through on her career path. He finally gets where he wants, when she dissected a man, the first naked man she saw, and the pleasure she felt when opening him with the scalpel. Mamiya does not implant an entirely new idea in the heads of his victims – if we can still call them that – but brings to the surface previously existing, perhaps repressed, thoughts. He does not use words or special objects, but simply what was already there.

Kyua is a film that takes place mostly behind closed doors. We have, of course, important exceptions that take place outside, such as the discussions between Takabe and Sakuma on the roof, or the wanderings of Fumie Takabe (Anna Nakagawa), the detective’s wife, around the city. But the film takes place, in essence, indoors, where the scene unfolds through the choreography of the characters and their interactions with objects, not very different from what it would be like on a theatrical stage. Mamiya’s work involves concentrating his victims’ gaze on the elements he manipulates and, to do so, requires a restricted space. The same can be said about Takabe’s investigation or interrogation work, which is also fraught with tension. This doesn’t mean that the film isn’t dynamic, the editing is probably what’s most expressive about these scenes, the precise moments when we finally move from long shots to close-ups, fixed shots to moving shots.

An interesting scene in this sense is Fumie’s first appearance. Here, at first, we do not have a malignant or investigative tension, but another type, disturbing precisely because it occurs within the family nucleus. We had already seen the character in the brief opening scene, in a psychiatric hospital, but not yet as the detective’s wife. Kenichi Takabe arrives home and turns on the lights, which we see through a doorway. A continuous noise increases as he opens another framed door, the one to the laundry room; the source of the noise reveals itself, a washing machine. He opens the lid of the machine and there is nothing inside. He goes to the kitchen, where he heats up his dinner in the microwave, which is waiting for him on the set table. It’s then that Fumie enters the frame, without us seeing very well from where, and greets her husband, who asks if he woke her up. Although there are signs that someone was already home – the washing machine, the table set -, Kenichi’s solitary arrival and Fumie’s omission at first are enough to make her sudden appearance ghost-like.

The camera then begins to move and follow Kenichi, while his wife walks back and forth around the house solving small tasks, almost as if she were avoiding the frame, also in a kind of trance. When Kenichi asks her what she did during the day, she tells him that she’s done nothing. Once she leaves the scene, we soon hear the sound of the washing machine again, which now seems to replicate Fumie’s hollow behavior.

Like Mamiya, Fumie maintains a vacant gaze, never meeting her husband’s eyes, and we soon realize that this is not the only similarity between the two. Her elusive attitude also seems to express a void, just as the antagonist declares when he says that “all the things that used to stay inside me are now outside”. The difference is that, while Mamiya reaches this condition voluntarily, studying hypnosis theories, Fumie’s case is clearly pathological, as the film makes it clear that the character has some psychiatric illness. If Mamiya empties himself in order to see and eventually control what’s inside others, Fumie’s situation is closer to that of his victims. Throughout the plot, she seems to constantly forget where she is going and wander around the lost city, as if she no longer owned herself.

Eventually, Kenichi Takabe himself will also lose control. At Mamiya’s house, located in the middle of a junkyard, Takabe encounters the transformative trajectory of this enigmatic figure, a former psychology student. The camera wanders through the young man’s bookshelf, first among studies on different personality disorders, passing through Carl Jung, and finally reaching the books of Franz Mesmer, a German doctor who coined mesmerism, or “animal magnetism” in the 18th century. This parapsychological theory, a precursor to hypnosis, believed that there was an invisible force within each living being that could be moved through hand movements for healing purposes. In another room in Mamiya’s house, Takabe finds, covered by a sheet, what we can understand as the practical unfolding of the theories studied: the corpse of a twisted monkey, pulled by strings like a marionette.

One of the books found by Takabe is titled “Mesmerism and the End of the Enlightenment in France” (by Robert Darnton), a curious title considering the obscure nature, both literal and metaphorical, of Kyua. If the detective plot usually tends towards clarification of facts, Kyua, like Mesmerism, will move in the opposite direction. Up to this point, we followed Takabe’s investigation parallel to Mamiya’s trajectory, a movement of elucidation against one of shading. It is precisely when Takabe believes he has won, captured the enemy, that the other prevails.

The visit to Mamiya’s origins signals a significant turn in the film. The case itself has already been solved, but something happens after the detective enters the house, as if that charged atmosphere allowed Mamiya to infiltrate not only the detective’s mind but the structure of the film. The first signs of infiltration occur in quick flashes of previous images that flicker as soon as Takabe leaves the house. Returning to his own, he finds his wife dead, hanging from the ceiling in an apparent suicide, a scene that lasts a few seconds until the detective snaps back to reality and realizes it was just a vision.

Angered by the intrusion, Takabe confronts Mamiya at the place where he is confined, a dark and isolated room, a perfect setting for the hypnotic process. There, Mamiya doesn’t even need to delve into the detective’s repressed thoughts; he already assumes, on his own, that his wife is a burden. Takabe seems equally drawn to and repelled by the process; we perceive a mixture of fear and desire in his vision of his dead wife. Mesmer’s hypnosis, after all, is considered a kind of healing through emptiness. “It will make you happy, empty,” says Mamiya. If Fumie’s mind seemed impenetrable to Takabe, his homicidal feelings towards her are also kept secret – just like in the tale of Bluebeard where the husband keeps secrets behind a closed door, the corpses of his ex-wives.

It’s difficult to pinpoint the exact moment when Takabe loses control of himself, or even if that actually happens, since the film also becomes increasingly elliptical. The order of the scenes, their concreteness, their objectivity, everything is called into question. If up to half of its duration the unfolding of this narrative was presented to us in a direct and even rigid way, albeit not always elucidative, everything starts to blur once the detective enters the epicenter of mesmerism. Kurosawa will follow this spiraling with such caution that the impression is that not even he would know where he was going to end up, as if he too had been taken by surprise by the darkness and intermittency that engulf the film. But all this was there from the beginning, lurking, in every cigarette ember, in every drip, in every poorly lit corner.

Paula Mermelstein Costa